Elevate Team Productivity: The Impact of Psychological Safety and Mutual Knowledge

Nov 14, 2020

By Stefano Mastrogiacomo

“We have too many meetings.” If you think or heard that, know that you're not alone.

The Reality of Unproductive Meetings

This common lamentation echoes across boardrooms and virtual meetings. Atlassian reports that a staggering 50% of meetings are deemed unproductive, culminating in a $37 billion salary wastage in the US alone. This startling inefficiency eerily mirrors tactics in the 1944 CIA’s Simple Sabotage Field Manual (photo below) - bloated committees, endless conferences, and incessant talking. Are we unwittingly sabotaging our own productivity?

The Foundations of Team Productivity

Contrary to the idea of intentional sabotage, the real issue lies in our collective negligence of teamwork fundamentals. Our focus on grandiose projects often overshadows the importance of everyday interactions. Two pivotal elements underpinning collective performance are:

1. Psychological Safety: A trust-based belief that interpersonal risk-taking is encouraged and safe in a team. Key indicators of neglect include distrust, fear of speaking up, disengagement, over-collaboration, and loss of team cohesion.

2. Mutual Knowledge: A shared understanding of team members’ knowledge, beliefs, and assumptions, facilitating transparent information flow and knowledge sharing. Symptoms of neglect include unclear roles, shifting priorities, project duplications, siloed work, and overlapping projects.

The Misconception About Meetings

While meetings are often criticized, they are merely a reflection of underlying issues - psychological safety and mutual knowledge neglect. It’s not about having fewer meetings, but about improving what we say and how we behave during them.

Dual Pillars of Team Effectiveness

To enhance team efficiency and creativity, foster psychological safety and mutual knowledge within your team. A Google study highlighted psychological safety as a key driver of high-performance teamwork, promoting productive dialogue and collaborative problem-solving. Conversely, teams with higher common ground execute tasks 4-12 times faster than those with insufficient common ground.

Implementing the Change

Over the past decade, we’ve developed simple, free tools to bolster your team’s mutual knowledge and create a safer environment.

The Team Contract

Establish team rules, behaviors, values, communication, and expectations around failure.

The Fact Finder

Transform unproductive assumptions, judgments, and generalizations into observable facts and experiences.

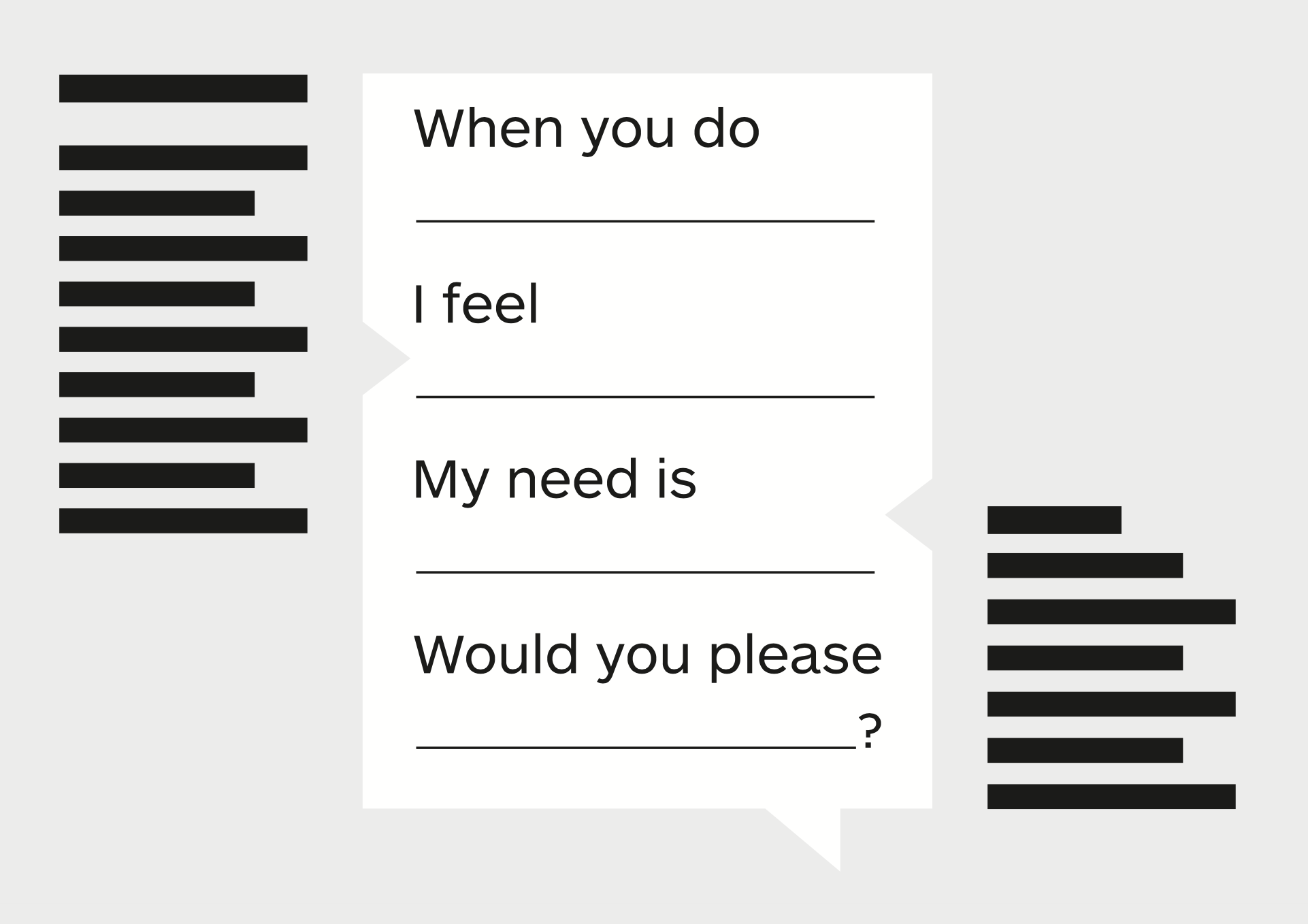

The Nonviolent Requests Guide

Manage conflicts constructively by expressing negative feelings empathetically and appropriately.

The Team Alignment Map

Co-plan the team mission, objectives, and responsibilities to boost common ground and engage members from the outset.

Take Action

Get your copy of Book - High-Impact Tools for Teams, Wiley, Strategyzer Series, 2021.

Download the Team Alignment Toolkit for free.

Credits

Illustrations by Severine Assous and BlexBolex. Illustrissimo.fr

References

Clark, H. H. (1996). Using language. Cambridge University Press.

Clark, H. H., & Brennan, S. E. (1991). Grounding in communication.

Clark, H. H., & Wilkes-Gibbs, D. (1986). Referring as a collaborative process. Cognition, 22(1), 1-39.

Duhigg, C. (2016). What Google learned from its quest to build the perfect team. The New York Times Magazine, 26, 2016.

Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative science quarterly, 44(2), 350-383.

Frazier, M. L., Fainshmidt, S., Klinger, R. L., Pezeshkan, A., & Vracheva, V. (2017). Psychological safety: A meta‐analytic review and extension. Personnel Psychology, 70(1), 113-165.

Lewis, D. K. (1969). Convention: A philosophical study. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

* Measured by TeamAlignment.Co using a variation of the tangram game (+100 pairs) presented in Clark, H. H., & Wilkes-Gibbs, D. (1986). Referring as a collaborative process. Cognition, 22(1), 1–39.

Schein, E. H., & Bennis, W. G. (1965). Personal and organizational change through group methods: The laboratory approach. New York: Wiley.

Schiffer, S. (1972). Meaning. Oxford University Press.

Stalnaker, R. C. (1978). Assertion. In Pragmatics (pp. 315-332). Brill.